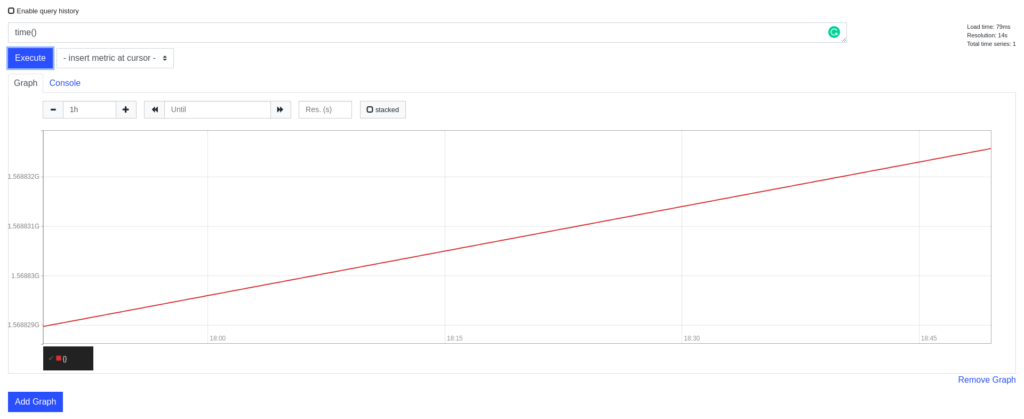

In the Cloud-based computing world, a relatively popular free and open-source software product called Prometheus exists which lets you monitor and observe other things. One of the components of its user interface lets you execute ad-hoc queries on the data that it has and see their results – not just in a table but also in a graphical way as well. For example, this is a query time() which plots the current time using two dimensions:

So, this gave me an idea some time ago: why not try to put some ASCII paintings in that interface and see how well Prometheus would be able to store them? And that is what I have done. To test this out, I needed to create a simple HTTP server which would serve the “metrics” which are actually the painting parts.

I have done it using the Rust programming language: additionally I got some experience in dealing with HTTP requests in it since I am still new to it. Lets continue talking about the actual realization of this thing. Note: if you ever have any trouble viewing the images then please right click on them and press View Image.

Implementation detail

Downsides

Immediately, a keen reader would have noticed that you cannot completely map the original ASCII paintings to the Prometheus interface since the characters could take any of the 255 different, possible forms, and we only have lines, albeit they can be with different colors, at our disposal.

However, the colors will be the representation of newline characters in the original painting. Thus, unfortunately, the different characters will have to be transformed into either 1 or 0 or, in other words, either a dot exists – the character is not space – or not.

So, we will inevitably lose some kind of information about the painting so it is a relatively lossy encoding scheme 🙁 But even in the face of it, lets continue on with our fun experiment.

Another thing to consider is the gap between different lines. Prometheus metrics have a floating point value attached to them. We could use 1naively everywhere as the value that we will add to separate two different lines however that will not get us very far ahead since the Prometheus UI automatically adapts the zoom level and the maximum values on the X/Y axis according to the retrieved data. This means that we might still have relatively big gaps even with that.

For that reason, we need to introduce some kind of “compression factor” into our application. Using it, we would be able to “squish” the painting more or “expand” it so that it would encompass more space at the expense of prettiness and recognizability.

Keeping that in mind, lets continue on to a example painting so that we would be able to see how it looks like.

Example

Lets start with the classical Tux penguin:

.-"""-.

' \

|,. ,-. |

|()L( ()| |

|,' `".| |

|.___.',| `

.j `--"' ` `.

/ ' ' \

/ / ` `.

/ / ` .

/ / l |

. , | |

,"`. .| |

_.' ``. | `..-'l

| `.`, | `.

| `. __.j )

|__ |--""___| ,-'

`"--...,+"""" `._,.-'

Our Prometheus will be configured with the following configuration:

---

global:

scrape_interval: 1s

scrape_configs:

- job_name: 'painter'

static_configs:

- targets: ['localhost:1234']

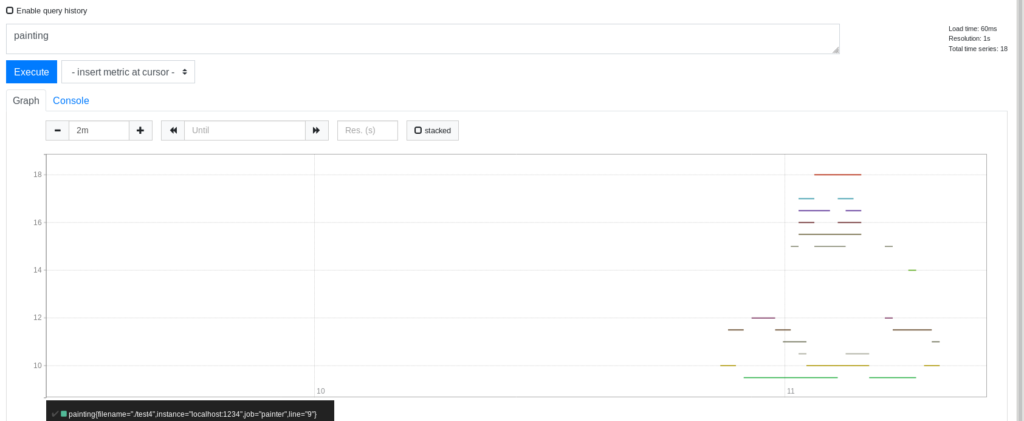

I have the scrape interval smaller so that it would take less time to ingest all of the painting into Prometheus. By running cargo run -- --input ./test4 I got the following result:

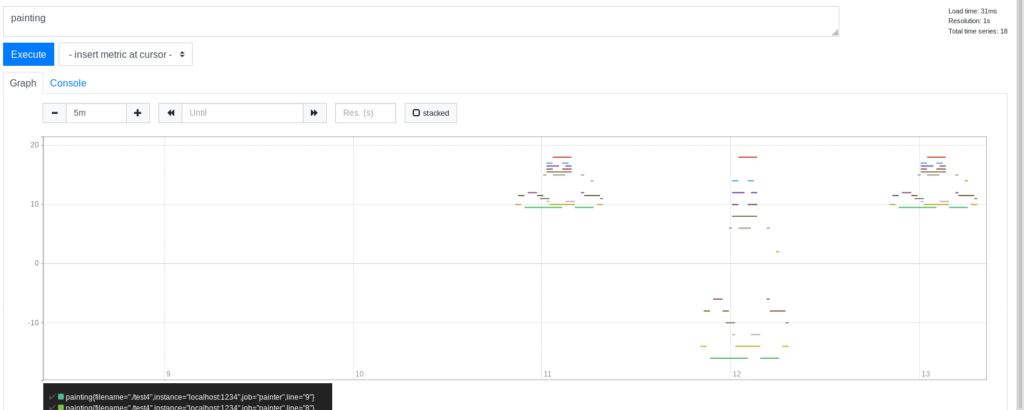

Now, lets try to compare the different compression factors and see how they play out in terms of the Prometheus query user interface:

On the left-most side we see the Tux penguin with the default compression factor i.e. 1 is used as the “gap”. In the middle, the Tux penguin became bigger by using compression factor 0.5 i.e. the penguin just became much bigger! However, as you can see, it became much harder to understand that we are still looking at the penguin. Lastly, the one on the right uses compression factor 2 or, in other words, 0.5 is used as the “gap” between lines. The penguin became much more legible in this case!

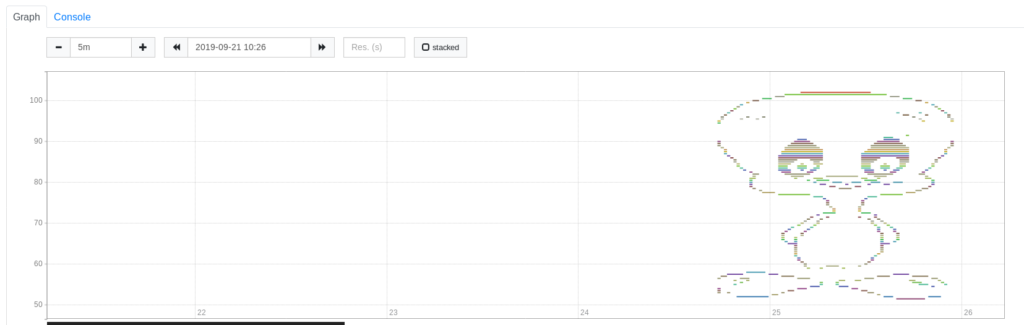

Lastly, lets try some kind of very big painting to see how well it fares in such situations as well. Try to guess what is this:

Yes, it is a duck! Here is the original ASCII:

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

XXXX XXXX

XXXX XXXX

XXX XXX

XX XX

XX XX

XX XX

XX XX

XX X XX

XX XX XX XX

XX XXX XX XX

XX XX XX XX XX

XX XX XX XX XX

XX X X XX XX

XX X X X

X X X X

X X 8 8 X

X 8 8 X

X 8 8 8 8 X

X 8 8 8 8 8 8 X

X 8 8 8 8 8 88 X

X 8 8 8 XXXX 8 X

X 8 XXXX XXXXX8 X

XX XXXXXX XXXXXXXX XX

XX XXXXXXXX XXXXXXXXXX XX

XX XXXXXXXXXX XXXXXXXXXXXX XX

XX XXXXXXXXXXXX XXXXXXXXXXXXX XX

XX XXXXXXXXXXXXX XXXXXXXXXXXXXX XX

XX XXXXXXXXXXXXXX XXXXXXXXXXXXXXX XX

XX XXXXXXXXXXXXXX XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX XX

XX XXXXXXXXXXXXXXX XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX XX

XX XXXXXXXXXXXXXXX XXXXXXX XXXXX XX

XX XXXXXXX XXXXX XXXXXX XXXX XX

XX XXXXXX XXX XXXXX XXXX XX

XX XXXXX 88 XXXX XXXX 88 XXX XX

XX XXXX 8888 XX XXXX 8888 XXX XX

XX XXXX 8888 XXX XXXX 8888 XXX XX

XX XXXXX 88 XXX XXXX 88 XXX XX

XX XXXX XXX XXXX XXX XX

XXX XXXXXXXXX XXXXXXXXX XXX

XX XXXXX XXXXXXXXXXX XXXXX XX

XXX XX XXXX XXX XX XXX

XX XX XXXXX XXXXX XX

XX X XX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XX

XX XXX XX XX XXX X XX

XX XXX XXX XX

XX XXXXX XXX

XX XXX

XXXXX XXXX

XXXXXXXXXXX XXXXXXXX

XXXX XXXX

XX XX

XX XX

XX XX

XX XX

XX XX

XX XX

XX XX

XXXXX XXXX

XX XX

XX X XX XX X XX

XX XX XX XX

XX XX XX XX

XX XX XX XX

XX XX XX XX

XX XX XX XX

XX XX XX XX

XX XX XX XX

XX XX XX XX

XX XX XX XX

XX XX XX XX

XX XX XX XX

XX XX XX XX

XXXX XXXX

XX XX

XX XX

XX XX

XX XX

XX XX

XX XX

XX XX

XX XX

XX XX

XX XX

XX XXXXX XX

XX XX XX X

X X X X

XXXXXXX X X X X

XXXXXX XXXX X X X X XXXXXX

XXX XXXXX X X X X XXXXX XXXXXX

XX XXXX XXXXX X X X XXXX XXX

X XX XX X XXX XXX XXX XX

X X XX XX XX XXXX XX

X X XX XX XX XXXX XX

X X X XXXX XXXX X XX X

XX X XXXX XXX X X X

XX X XXX XXX X X X

XX XX XX XXX X X X

X XXX XX X X X

XXXXXXXXXXX XXXX XXXXX

XXXXXXXXXXTaken from ASCIIWorld.

Disk usage comparison

Lets try to compare how much it takes to store the Tux image used before, for example. Also, note that Prometheus by itself stores some “meta” metrics about its internal state such as the metric up which shows what jobs were up and if they were successfully scraped or not.

By itself the Tux painting has 464 bytes of data. I ran Prometheus again and “painted” the ASCII picture there. The end result is that for storing all of it + some meta metrics it takes 10232 bytes of disk space.

Given that it is such a lossy encoding scheme and that it takes ~25 more times to store the same picture of Tux we can safely conclude that it is not a good idea to store our paintings there.

Future

Perhaps we could take this concept even further and write a FUSE filesystem for Linux which would store all of this data in Prometheus? We have all of the needed components: we are able to store ones and zeros, and one other symbol to separate between different “parts”. Plus, this filesystem would also provide a very “futuristic” feature – we would be able to travel back in time to see how the contents of the disk have changed.

On the other hand, spurious network problems could lead to data loss since Prometheus would not be able to scrape all of the metrics. So perhaps this idea should be abandoned after all unless someone wants to do such an experiment.

You can find all of the source code here! Do not hesitate to comment or share this if you have enjoyed it.